Early-Stage Brand Strategy: Where’s The Pop In popchips’ Sales?

In 2007, popchips launched to a very intense media blitz that continued for several years as the brand’s sales seemed to be on a high-growth, early-stage path to stardom. The model for the brand was glacéau vitaminwater, whose sales grew at phenomenal rates, reaching $350M before Coca-Cola acquired it in 2007.

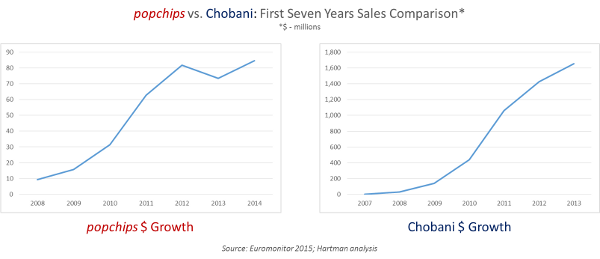

Yet as of the end of last year, popchips’ U.S. retail sales were struggling to sustain the growth rate of the early years. This is true despite very heavy PR saturation, a great trademark, four different celebrity endorsements and apparently very broad distribution ranging from C-stores to Costco.

The apparent deceleration of popchips may not be the end of growth, but it does raise a critical issue in the strategy playbook of early-stage brands.

As we can see, Chobani had crossed $200M in sales by the end of its third year of conventional distribution, giving it enormous momentum with the retail trade across the country. Popchips has not scaled nearly as well in a similar timeframe. In the meantime, they have allowed a host of CPG players, including the key incumbent, Lay’s, to copy their idea.

What constitutes sufficient ‘innovation’ for an early-stage brand to accelerate growth and not get quickly mimicked by established brand players with larger R&D, sales and distribution assets?

One might call this “the Chobani principle,” and it is important to consider it prior to investing big in early-stage concepts. While most premium brands won’t scale as large as Chobani, learning from its strategic positioning is possible.

Most CPG companies have little interest in acquiring a premium brand, regardless of fast growth, when their own plants could easily produce the product and when their power brands could credibly extend into the space (including via copackers).

Where early-stage brands have the best chance to scale quickly is when they threaten the margin model of the legacy market share leaders (e.g., natural/organic formulas in established categories with lots of processing, higher-quality ingredient inputs) or when the sensory experience, nutritional profile or flavors are too non-mainstream to garner large Y1 trial in CPG concept tests. In both cases, the CPG incumbent will have a hard time accepting even the most powerful market research in the product’s favor. This gives an early-stage brand appropriate runway space to accelerate distribution slowly, build buzz among consumers and then hit the $200-300M in sales mark before CPG incumbents can react. It will then take them two more years to get their own product to market. In fact, a stealthy go-to-market, with only local PR/marketing, is advised so as to not tip off the larger players.

The challenge we see with popchips is that it fundamentally did not have the right barriers to CPG entry on its side. Popchips primarily benefited early on because the recession distracted large players from following for the first four years. In fact, popchips is a product easily mimicked by copackers around the country, and it had no other ‘non-mainstream,’ yet trendy, characteristics that would prevent it from doing well in conventional CPG concept tests. It also attracted enormous attention to itself early on with ‘mainstream’ celebrity endorsers like Ashton Kutcher and lots of national PR. It was literally inviting the big brands, like Frito-Lay, to the national stage.

Chobani, on the other hand, had multiple properties that would have put off, and did put off, the major yogurt incumbents: a distinct flavor and texture profile; it sold satiety in a ‘diet category.’ It was selling high-protein/low-sugar nutritional profile before conventional CPG market research indicated this trade-off was even a problem. This is the kind of barrier to rapid CPG entry a premium startup requires to keep major CPG competition away as it slowly seduces the retail trade.

Popchips is now in a situation where it must engage in expensive marketing campaigns to survive and grow, and it must leverage unconventional channels of distribution where Frito-Lay has no way to dominate access (i.e., e-commerce). This is not an ideal situation. But with superb marketing, we see no reason why popchips’ sales could not get to at least $200M eventually.