Putting Brand in Its Place — The Role of Brand in the Product Life Cycle

As the largest single advertising day of the year approaches, key food and beverage marketers are crossing their fingers that their large Super Bowl promotional investments will reap significant lift at the shelf. This is a hallowed annual ritual in American marketing. Even the most cynical and jaded of consumers can’t help but be interested to know which ad will push the limits of creative persuasion.

As the largest single advertising day of the year approaches, key food and beverage marketers are crossing their fingers that their large Super Bowl promotional investments will reap significant lift at the shelf. This is a hallowed annual ritual in American marketing. Even the most cynical and jaded of consumers can’t help but be interested to know which ad will push the limits of creative persuasion.

The vast majority of the Super Bowl spending we see each year goes to support legacy brands. In the case of the annual sponsor, virtually every communications touch point is ‘on brand’ in what is now one of the most complicated, highly choreographed, multiscreen promotional campaigns one could possibly devise.

The Super Bowl is a cultural celebration of the art of branding. The NFL brand itself is fiercely defended, promoted and spread.

But years of ethnographic research have taught us to question the deafeningly silent implication behind all of this effort: that brand is always a top purchase driver and the engine of growth. This would seem to be so obviously true in CPG marketing, it is not worth questioning. The problem is: it isn’t.

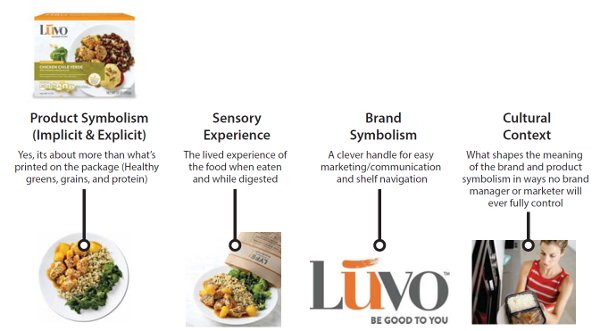

The key to breaking through this assumption and managing a specific product line accordingly is to understand the layers of meaning and experience that a branded packaged food contains.

Here is what we find when we deconstruct your average UPC like an archeologist would:

What our ethnographic research has found consistently is that brand is actually one of many symbolic layers of experience affecting both trial and repeat purchase in consumer food and beverage brands. In today’s more complex, sophisticated food culture, brand is now critical only in specific stages of the product life cycle, namely what we term the mid stage and the late stage (HB Exec Q4 2013). But it matters very little in the beginning and not too much in the end, either (if the brand was helping much, the business would generally not be collapsing).

What has caused many legacy food brands’ growth to stall and/or reverse itself in recent years is that the symbolic elements surrounding the food (i.e., the product symbolism) are fundamentally undercutting the business in a way that no advertising campaign or brand renovation can ameliorate. This is especially the case when a brand has an iconic flavor/texture among heavy users that is simply anchored in the past. In these cases, the symbolic elements of the product and sensory experience cannot be easily changed without alienating the brand’s fan base. So, even as loyalists cling, albeit in smaller and smaller numbers, there often can be no real way out.

Coming to terms with this role of brand and the legacy role of outdated product symbolism is critical in distinguishing between brands that are: a) capable of renovation in their product symbolism vs. b) brands that most likely are victims of an iconic arrangement of product symbolism anchored to a prior era.

In other words, just because your brand is at the Super Bowl, that does not mean the symbolism of its UPCs is playing to win.

Download the free Hartbeat Exec: Role of Brand in the Product Life Cycle