The Product Life Cycle and Its Role in 21st-Century Portfolio Strategy

With the recent acquisitions of KeVita and Bai beverages by major CPG players, it is clear to us now more than ever before that modern portfolio strategy has more or less accepted the necessity of bringing younger, premium brands into the portfolio as a long-term growth strategy.

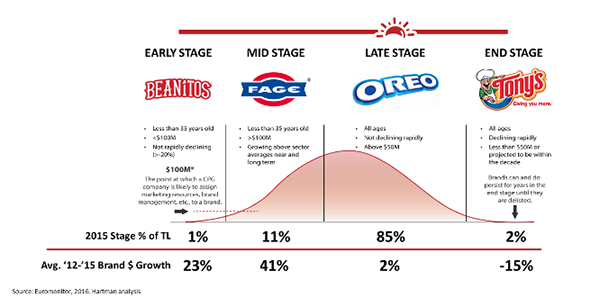

But when in the life cycle should this be done?

The disposition of major CPG firms is still weighted toward acquiring younger brands with sales in excess of $100M — but how companies get there is changing due to the hypercompetitive marketplace for early-stage brands.

Both recent beverage acquisitions represent the virtue in minority investments early on in the revenue growth of young brands deemed to have high potential for scaling.

Yet other firms, like Hershey, have shown that acquiring as low as $20-30M may be required in the most competitive sectors of food and beverage to keep overall costs down on what is still, ultimately, one growth bet among many a company is having to fund.

In other words, if you’re trying to acquire for reasonable costs, it is not possible to actually wait until a young brand has reached what we term the mid-stage to reach out and strike a deal. You will have already been beaten by other suitors.

But there is additional value in acquiring younger brands during the early stage. And that is the intangible value of being able to gain control of the business and fine-tune its marketing, distribution and R&D before VC or founders try to accelerate growth ‘by any means’ just to generate a sale. There is also the value of buying a younger brand at its more vulnerable stage of development where the fundamentally different consumer and go-to-market dynamics of premium brands are easier to learn and embrace within the organization. When your brand has less than 10% HH awareness, you fundamentally can’t succeed with mass market distribution plays easily executed by high-performing legacy-brand extensions. This becomes readily apparent when sales teams try to artificially throttle up early-stage brand distribution before it is warranted.

Portfolio strategy has clearly embraced the need for bringing younger, premium brands into the portfolio. But what we’re not seeing is the development of a separate go-to-market playbook for these businesses as they grow through the early stage and into the mid-stage.

It is the organization’s ability to develop such a playbook, we’re finding, that appears to determine its ability to successfully scale within the kind of distribution environment offered by a large company. Part of the ‘collective playbook’ that successful premium brands use includes recognizing early on in the life of the business whether or not there is a fatal flaw in product design that may prevent scaling (e.g., sensory nonstarters) or cause a consumer backfire (e.g., becoming seen as an impostor). This can be successfully addressed only in the early stage to avoid accumulating the wrong consumers or consumers (and retailers) who will soon be disappointed.

Acquiring younger, premium brands at a reasonable cost is one increasingly challenging feat. But it pales in comparison to learning how to scale premium brands carefully and maximize revenue creation as the business grows distribution. This is an art traditional line and general managers often never learned but increasingly are being asked to learn.

For more information on how we train companies on the art and science of premium go-to-market strategy for early-stage brands, contact Shelley Balanko