Today’s Hot Topic: FDA’s New Nutrition Facts Panel: Small Changes in a Vast Arena

The U.S. Food & Drug Administration made big news recently when it proposed changes to the Nutrition Facts Panel (NFP) on food and beverage products. Although consumers rarely scrutinize nutrition facts panels, they are an important source of information for evaluating healthfulness among people who read product labels. The Hartman Group decided to explore two of the changes with consumers:

The U.S. Food & Drug Administration made big news recently when it proposed changes to the Nutrition Facts Panel (NFP) on food and beverage products. Although consumers rarely scrutinize nutrition facts panels, they are an important source of information for evaluating healthfulness among people who read product labels. The Hartman Group decided to explore two of the changes with consumers:

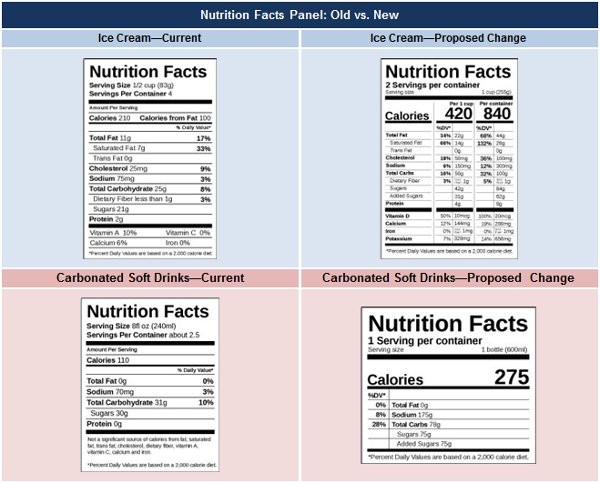

1) Serving-size data: Food-forward consumers are skeptical about the labels and serving-size data. For example, many scoff at 22-ounce bottles of soda claiming to contain 2.5 servings. Now that the FDA is calling for serving sizes to reflect reality, will consumers evaluate the panel differently?

2) Added sugars: Michelle Obama’s pet peeve is the lack of information about added sugars in many processed foods, although consumers concerned about sugar can already tell a lot when it’s listed as a top ingredient. How will consumers react to an additional callout mandated by the FDA?

These changes likely are aimed at about 25 percent of consumers, people unconcerned enough about what’s in their food that they do not do serving-size math or evaluate ingredient lists. It is the same group of “nutrition sinners” that many public-health efforts attempt to reach. But that audience isn’t listening, because it doesn’t have a proactive stance on health and well-being.

To understand how the general population might react to the proposed new nutrition panels, The Hartman Group conducted an experimental test online. We showed consumers current panels for ice cream and soda and proposed panels for the same products, featuring revised serving-size data and the inclusion of added-sugar information.

We deliberately chose foods for which the distinction between currently stated serving size and consumers’ actual behavioral serving is large and where added sugars are highly relevant—then we asked them to tell us in their own words the most important features of the panels for each product.

The top concerns for both categories were identical, regardless of panel design. With the new design, people seldom mentioned added sugars, and 7 percent or fewer mentioned serving size—the same rate as for readers of the current design.

In other words, the new nutritional panel design is not likely to alter product perception, because it will not be used differently by consumers.

As previous Hartman Group research indicates, the nutrition panel is just one of many information sources that concerned consumers use to make informed decisions. Their friends’ beliefs are far more important. When soda sales declined because health-minded consumers started to believe that drinking liquid sugar is a setup for health problems, it was because their immediate social environment taught them that, not because a scientist made the case or a public health official planted a sign near their YMCA.

Although it’s heartening that the nutrition facts panel is evolving to be more in line with what users want and need, the panel is no longer at the leading edge of America’s health and wellness evolution. People no longer need to be educated about the basic macro-nutrient realities of most foods, since they already know that information in a way that’s suited to their nutritional goals. Consumers who want more information also have many other places to look.

Just as social pressure led people to abandon smoking on a large scale, intimate social pressure is one of the most effective processes for effecting dietary change. The bottom line is that change is best effected through culture, not educational campaigns in the supermarket aisle.

Hartman Insights Classics: What’s on the Label? How Consumers Understand Food Labeling

The Hartman Group knows food labels. It has researched and written extensively about how consumers use labels and what they want from them. Today’s Hartbeat features consumer reactions to proposed changes to federally mandated nutrition facts panels. Here are insights from earlier research that still hold true:

The Hartman Group knows food labels. It has researched and written extensively about how consumers use labels and what they want from them. Today’s Hartbeat features consumer reactions to proposed changes to federally mandated nutrition facts panels. Here are insights from earlier research that still hold true:

“In food labeling, there will continue to be strong inclinations to communicate as transparently as possible about various product attributes (‘Now with more Whole Grain’), to attempt to correct for what are viewed as former shortcomings (‘Now with Less Sugar’) and to very likely shorten ingredient lists.” 2006, Transparency: What’s Really Inside the Package—and the Company

“Label reading itself may soon be classified as a lifestyle hobby, with a diversity of influences driving consumers to "learn" (or ignore) certain elements of a package. While specific influences tend to tip consumers to consult label components carefully, rising interests in freshness, authentic product narratives and the origin of ingredients speak for interesting times ahead for manufacturers and retailers seeking to influence consumers by package design.” 2007, Label Profusion

“Be sure that your natural foods and beverages have an ingredient list and nutrition facts panel that align with the consumer ideal: Healthy choices with a short, recognizable ingredient list with nothing artificial, no preservatives, additives or fillers.” 2010, Where Organic Ends and Natural Begins

“The time has come to stop focusing on just the parts, which to date have included education on packaging and nutritional panels, placing the blame on manufacturers and QSRs, and noting the availability of "bad" food; instead, we must start to focus on the whole, which is essentially a cumulation of how we, as Americans, eat and its direct effect on how much we're eating.” 2012, Those Who Eat Together Fight Obesity Together