HEALTHY, “NATURAL” AND THE FDA: A DEFINITION PROBLEM. WE’VE SEEN THIS BEFORE.

What is a “natural” food? The recent announcement by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that it resolved a yearlong tussle with KIND Healthy Snacks over the use of the term “healthy” on KIND’s food product packaging has rekindled the decades-old challenge for the FDA to define what a “natural” food is.

What is a “natural” food? The recent announcement by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that it resolved a yearlong tussle with KIND Healthy Snacks over the use of the term “healthy” on KIND’s food product packaging has rekindled the decades-old challenge for the FDA to define what a “natural” food is.

The world of natural food, and the natural products industry in general, has historically been plagued by a lack of public consensus on the definition of “natural.” In addition, consumers have been confused about the possible wellness benefits derived from participation in the natural foods product world. Part of this confusion stems from definition problems.

Whether through deep engagement with food culture and the worlds of health and wellness or by virtue of passing encounters with free-flowing information streaming from ever-multiplying channels, today’s consumers are increasingly aware of the personal, social, environmental and health consequences of the foods they consume. While the increased availability and proliferation of organic and natural products across categories fuel consumers’ aspirations, in a climate awash in confusing and conflicting information, consumers are questioning products, companies and certifications more than ever before.

This is why consumers are increasingly seeking answers to: What’s in it? How was it made? Who made it? What’s the story behind it? What does it (e.g., organic, natural, healthy) mean?

We’ve Been Here Before

Bringing clarity to the confusion about the definition of natural and organic is a story more than 25 years in the making. From The Hartman Group’s first days in 1989, we’ve been researching and tracking the evolution of consumers’ understanding of natural and organic. Over time, we’ve witnessed the definitional disputes that have plagued the food and beverage industry (in general) and the natural and organic industry (specifically).

While the decade of the 1980s was about the emergence of awareness of the environment and the 1990s was the decade of the rise in natural, the dawn of a new millennium in 2000 brought us a new era focused on health and wellness. Food has become a keystone of health and wellness, with people preferring to receive nutrients through foods and beverages rather than supplements or functional foods.

Throughout these transformative decades, natural was an orientation people assumed in the pursuit of health and wellness. This is still true today as natural food and beverage products have become more integral to the pursuit of higher-quality lifestyles.

Because wellness is now firmly embedded in the culture — it’s inherent in the way people shop, cook and eat — organic and natural products have become so ubiquitous that specialty and natural products retailers now need to offer something more to maintain their appeal and relevance.

Yet while the ideal of “natural” continues to evoke positive associations and an image of simple, real food that is free from artificial ingredients, consumers are increasingly primed to react to the term as a marketing gimmick.

As a package claim, natural immediately raises red flags. When confronted with a product that claims to be “natural,” consumers turn to the ingredient panel and nutrition facts for the truth.

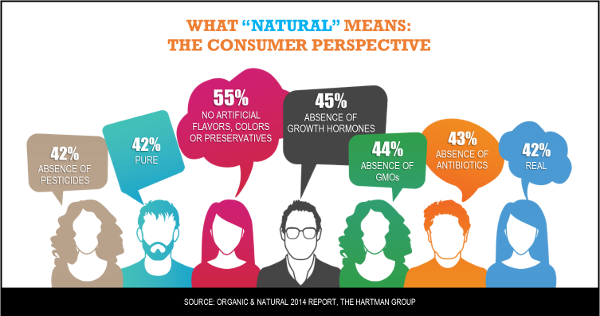

With the proliferation of organic and natural foods and beverages in the mainstream, their meaning has shifted. While the meaning of organic has weakened in the past few years, natural is experiencing renewed significance. The following chart depicts the attributes consumers associate with the term "natural."

Consumers are seeking an ideal of natural that would mean that the food and beverages they buy are healthy, whole, real and minimally processed. Natural is understood as what happens to the food after it is grown, specifically regarding the reduction of processing steps.

Consumers more strongly associate “no artificial colors, flavors or preservatives” with natural, illustrating the solid connection between natural and production and processing. While consumers associate “natural” with an ideal of minimal processing, they do not believe that the word “natural” ensures that foods and beverages live up to the ideal that they are seeking. This is why the use of “natural” on packaging elicits skepticism toward its usage as a marketing ploy and encourages consumers to investigate the product more. It is not enough alone, however, to ensure that the product lives up to their ideal. According to The Hartman Group’s research, 59 percent of consumers would most like the government to regulate which products are labeled “natural.”

What Can We Learn From This?

For natural products it is essential to live up to the ideal of natural that consumers are seeking regarding production and processing. To the untrained eye, for example, the product may be a box of cereal, but to the average consumer it is a field, a farm, a factory.

Today’s consumers have taken it upon themselves to figure out what natural means to them. They look for a combination of subtle cues. Ingredient lists and nutrition facts panels should align with the consumer’s ideal of natural and healthy foods and beverages.

No one is waiting for food regulators to solve the dilemma; consumers are companies’ regulators. Companies that understand consumers’ expectations and how language and product design work together to form impressions of “natural” and “healthy” and other virtues will free themselves of the regulator-inspired habit of trying to make explicit “claims” about what are typically vague quality distinctions of what is natural and healthy. Removing symbols of bad or low-quality food processing is critical to keeping a brand contemporary in modern food culture.