Snacking Culture: Consumers Take Control of Portion Sizing

More than a decade has elapsed since we reported on consumers’ struggles with controlling portioning sizing as a primary hurdle to proper eating habits as well as a more general cause of being overweight or obese. At the time, consumers looked to companies for help, and consumer packaged goods food companies responded with an array of packaged 100-calorie “portion control” snacks. While this seemed like a practical solution at the time, the problem was not one of the package size but one of human behavior: the actual activity of regulating portion sizes proves significantly more challenging.

More than a decade has elapsed since we reported on consumers’ struggles with controlling portioning sizing as a primary hurdle to proper eating habits as well as a more general cause of being overweight or obese. At the time, consumers looked to companies for help, and consumer packaged goods food companies responded with an array of packaged 100-calorie “portion control” snacks. While this seemed like a practical solution at the time, the problem was not one of the package size but one of human behavior: the actual activity of regulating portion sizes proves significantly more challenging.

Today, the cultural saga continues. Reduced-portion sizes of food and beverage products (a significant growth segment of the restaurant industry) can be found in abundance, and yet consumers still struggle with controlling intake. What is different now is that consumer eating behavior is shifting profoundly from one of ceding diet control to third parties (e.g., consumer packaged goods manufacturers and restaurant/food service) to self-directed ambitions to regulate eating and drinking behaviors.

Many consumers simply perceive that they are more than capable of controlling portions. They want the ability to decide the sizes of the portions for themselves, rather than have it dictated for them by outside parties. Yet self-control remains a struggle: our Health & Wellness 2015 report finds that more than a quarter of consumers (27 percent) cite that one of the chief roadblocks to eating more healthfully when dining out is that portion sizing at the restaurant is “larger than what is healthy for me.”

As with any cultural shift in eating behavior, the answers as to why portion control has become more of a personal practice are complex and rooted in large-scale changes we are experiencing as we move from a traditional eating culture to a “modern” eating culture.

Our Culture of Food 2015: New Appetites, New Routines report sheds light on how eating culture is changing, with resulting impacts on dieting and eating practices.

In traditional eating culture:

- Well-defined meals carried the primary burden of our physical, social and emotional needs

- Breakfast, lunch and dinner were narrowly defined in terms of:

- What we ate: dishes, types of foods, familiar flavor profiles

- How much we ate: typically substantial, hearty portions

- When we ate: socially defined times (much like clockwork)

In today’s modern eating culture:

- There are fewer rules about what to eat and drink (think: “snacks” or “mini-meals”)

- Food decisions are driven by availability, wants and whims, aspirations and ethics

- We’re more conscious of health outcomes when choosing what to eat, and we often idealize having three balanced meals a day, yet rarely actually eat that way

- The snacking “between moments” have become as culturally prominent as meals, and the definition of snacking is also evolving

|

Snacking behaviors themselves are having a profound impact on the entire realm of portion control. With half of all eating occasions defined as “snacks” by consumers, we can see that new definitions of “meals vs. snacks” have a direct impact on judgments about portions themselves. Despite fluid definitions around what constitutes a “snack,” consumers associate snacking with a few defining characteristics. In describing their eating and drinking, individuals divide their “food life” into meals and snacks, with little other terminology. Which side of the line a consumption occasion falls on is determined by a hierarchy of factors.

Size is the most salient factor that classifies an eating occasion as a snack. Even if “small eating” happens at a mealtime, it is often thought of as a stand-in until the next “large eating.” For “snacks,” those include:

- Between times. Snacks intuitively fall in the gray areas between socially/culturally assigned “mealtimes”

- What’s eaten. While anything can be a snack, certain categories are more culturally ascribed to snacking occasions (e.g., bars; salty, crunchable foods; single item produce; packaged sweets; single-serve packaged items; ancillary categories like dips or spreads; any single meal component)

- Lowest prep and cleanup. Snacks typically involve little to no construction or preparation; any heating is brief and unattended

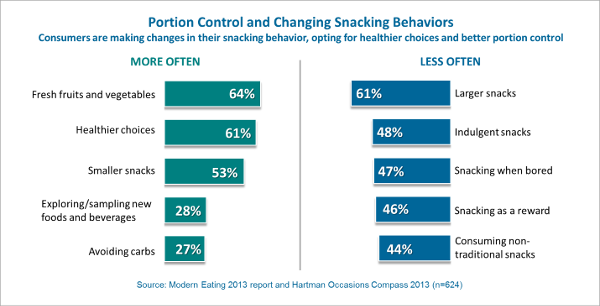

As snacking has increased in popularity, portion control has become an intrinsic part of consumers’ naturally regulating their diet and eating according to personal health, wellness and culinary goals. Manufacturers, food retailers and marketers can stay in step with changing eating behaviors by innovating outside the rigid confines of a single eating occasion or terminology and creating products designed to serve multiple needs and people—a part of which includes new ways to “control portions.”

For an in-depth look at snacking behaviors: