Soylent: The Future of "Replacing" the Meal or Replacing the Joy of Eating?

Powdered breakfast drinks in the 1970s. “Diet” shakes in the 1980s. Atkins protein shakes in the 2000s. Homemade fruit smoothies followed. And now Soylent.

Powdered breakfast drinks in the 1970s. “Diet” shakes in the 1980s. Atkins protein shakes in the 2000s. Homemade fruit smoothies followed. And now Soylent.

For several decades Americans have experimented with specialized health beverages designed to completely replace the meal.

Most recently, Rob Rhinehart, a tech entrepreneur who became frustrated with the cost of groceries, spent countless hours designing his own meal replacement beverage, complete with oil to provide healthy fats. The difference between Soylent and its less complicated predecessors is that its founder claims you can live on nothing but Soylent. He’s bucking the trend toward fresher, less processed food and believes food should be more industrialized. Rhinehart postulates that one should not have to worry about food ever again. Is Soylent connecting to something in contemporary food culture others have overlooked? A desire, on occasion, to eliminate conventional food?

Per capita consumed volume of traditional meal replacement beverages (all variants on a soy protein shake) in the U.S. is nearly half what it was in the year 2000 (according to Euromonitor). So, the traditional diet and weight maintenance shakes of yesteryear are generally not gaining real growth in usage, despite population growth over the same period.

Is it possible that the notion of the meal replacement might be turning a corner? Is the new generation (Orgain, Svelte, Soylent) finally what is needed to unleash growth in this behavior?

Let’s start by asking: What is the scale of meal replacement behavior today? And is it growing?

After decades of marketing by Ensure, Boost, SlimFast and the like, we consume these products very rarely. In 2014, only 1.8 percent of adult breakfasts were simply beverages. But even this number is misleading, because only one-third of these liquid breakfasts actually involved a beverage that offers substantial calories AND nutrition (e.g., yogurt smoothies, fruit smoothies, meal replacement beverages). The rest were low- to no-calorie drinks (water, coffee, juice), revealing that breakfast was more skipped than partaken. Less than 1 percent of American adult breakfasts qualify as pure liquid nutritive meal replacement. And, most importantly, there is no statistically significant growth (or decline) we can find in this behavior in the past four years.

But replacing meals is somewhat in the eye of the beholder. Is it about a simple substitution that can be clearly marketed to or is it about something else?

For two decades, we have been observing consumers treat bars much like the diet shakes of the 1980s. Certainly, they offer ‘meal replacers’ the satisfaction of chewing something, even if it is not very satisfying in the end compared to a hot meal. Here, the participation is much larger. In the past four years, 1.7 percent of breakfasts involved nothing but bars (i.e., a meal replacement by intent or happenstance; source: Hartman Food & Beverage Occasions Compass, 2011-2014; n= 75,966 eatings). The numbers for lunch and dinner are too small to be mentioned. Still, this is awfully small, given the enormous size of the bar category itself.

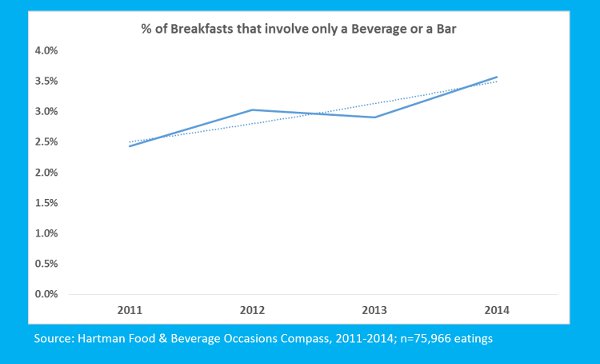

If we combine bars and qualified beverages, we see that perhaps 2.4 percent of American breakfasts are replaced each year by non-traditional replacement foods that have been engineered to do so. And with bars added to beverages, we see that, at least on breakfast, we have a statistically significant, steady increase in meal replacing behavior. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Clearly, we are warming up, slowly, to the idea of replacing traditional meals and meal prep with a single, easily consumed food/beverage. But how much longer could our interest here grow? The question really should be: How utilitarian are we prepared to make our meals as a society, especially dinner? How much can we reduce them to a purely rational act of nutrient onboarding? We are not here to offer a prediction but rather to unpack the insights one might sift through to make a strategic guess.

Orientations to Eating

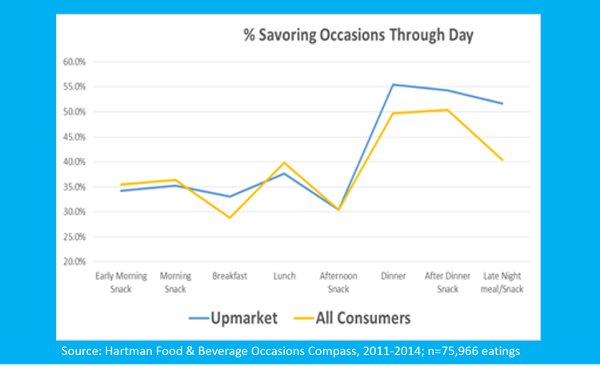

Let’s look at the orientation to eating throughout the day and week. America’s consumers transition from a more utilitarian to a more savoring (eating for enjoyment) orientation to food as the day progresses. This has been the legacy for decades of cereal marketing in the 20th century, which has trained many of us to have very rational nutritional goals in the morning. Later in the day, we tend to drift away from these nutritional goals. When we look at the upmarket consumer, this daily transition is the most dramatic. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Orientations to Eating Throughout the Day

When we look at these fluctuations across the week, we see that upmarket consumers also display the wildest fluctuations in their commitment to savoring, from day to day. Our ethnographic research among this group suggests that the upmarket consumer’s undulating orientation to food (an exaggeration of a Pan-American orientation) is because the upmarket social world is the most extreme in its pursuit of work and leisure (i.e., deprioritizing meal ritual) and also most extreme, ironically, in its pursuit of a reimagined foodway based on fresh, real and inspiring foods and beverages. They desire to savor good food (from specialty channels), but they don’t prioritize the time and effort involved in high-quality meal production. We clearly experience low-value meals on a regular basis that are ripe to be reduced to a beverage or a single, easily consumed, RTE food form. And that meal is most often breakfast.

But what about lunch and dinner? Are they so easily replaced in this way in our contemporary culture? We have elsewhere documented the erosion of meal ritual through the growth in daily snacking, the decline in individuals eating the same food at meals (due to catering to individual preferences) and the shrinking of household size. Meals, as cultural acts, no longer monopolize or control calorie dispersal or intake. We are very willing to skip breakfast or lunch, or demote dinner into a solitary act of reheating leftovers, all based on our more important priorities: work and leisure. And these priorities do not show any sign of shifting radically back toward extensive meal preparation and consumption rituals of the past. We generally treat our meals today both as flexible and optional, but we hardly seem interested in abandoning them. As a whole, Americans still tend to finish the day by savoring (and chewing). We stubbornly cling to dinner, above all, as the moment where we must eat something real.

Our data suggests that the future of meals, even the highly utilitarian breakfast, will be less about a rational process of substituting them with a single magic food or beverage than it will be a process of breaking down the ritual qualities of meals so that individuals can constantly tailor what they are eating (and drinking) to their needs at the moment.

This on-demand tailoring quality to meal composition is ultimately what marketers need to focus on, as much as the growth in breakfast meal replacing behavior. This loosening up of meal ritual is a trend that works against selling multiserve meal products and one that favors the growth of single-serve or dual-serve portions, since these can be more flexibly integrated into modular meals that serve fragmented tastes. It also favors customization-friendly QSR chains where the menu is not fixed but is rather a set of permutations.

Our very undulated approach to eating (at the daily and weekly level) allows so much bandwidth between the utilitarian and the epicurean that there is the likelihood that an increase in enjoying well-made, real, less processed meals will coincide for a long time, even on the same day, with highly utilitarian breakfasts we frequently enjoy. In fact, the growth in convenience services designed to deliver fresh meals or meal kits will only strengthen the ability for us to savor our dinners (and work lunches) in the years to come.

In the deritualized, snack-oriented food culture of today, there is no real cultural need for one merchandising category to function as a meal replacement. While some may argue that the decline in meal replacement beverages is due to their quality or design, we would argue it is simply because the growth in snacking and loosening of meal ritual offer many, many possibilities for replacing traditional meals with existing snack foods (and, yes, beverages). The term “meal” itself has morphed so that replacing it is frankly not as big of a cultural deal as it was in the days when Carnation Instant Breakfast launched into a food culture where snacking was rare and meals delivered most of our calories. There is less at stake in any given meal these days, which is why they are most often replaced not by specific categories but by the opposite of the meal: snacking.